The Back Lakes of Canada - January 1, 1874

A Deer Hunting Adventure and a 50 mile Expedition by Canoe

The Back Lakes of Canada

As was their custom, several young men of the town of Cobourg (a Canadian frontier town) met one evening in Frank Stalwart's rooms at the "North American." This was in the latter days of August, four years ago — yes, it must be four years ago, and yet how fresh in my memory, in spite of the many changes, some so gladly welcomed and others so ruthlessly bitter, which have since then transpired. On this particular evening the usual gossip was almost exhausted, when Ned Benton, a young, but not briefless, barrister, proposed we should settle upon the manner in which to take a couple of weeks' recreation.

Placing his pipe carefully against a book on the table, which I remember was Longfellow's Poems, my friend, Frank Stalwart, suggested a trip up the Back Lakes. Said he, "we can have a little deer hunting, a good deal of duck shooting, no end of fishing, and altogether a splendid outing." "Some prefer to 'ball it' at a watering place; what say you, Bob Bertram?" addressing myself, "and put down that novel and order in some claret and ice." "Well," I said, "I know not whether the claret will change my mind, but now I am for the Lakes. I have heard so much about their romantic scenery that I greatly desire to see them." So, it was settled that we should start on the following Monday, after having taken another evening to arrange the route and the requirements of our outfit.

Ned Benton and I, according to a previous understanding, met our companion, Frank Stalwart, at Peterborough, about thirty-five miles north of our starting point. This was done so that our friend could go by way of Rice Lake and bring over Thad. Fremont, an accomplished man in the way of dogs, canoes, and camp life on the lakes and in the woods. I may mention here that, besides his many other admirable qualifications, in all things culinary Thad. was a perfect success.

During the afternoon of the day of our arrival at Peterborough we proceeded to get together such things as are necessary for the hunter's outfit. Besides the tent, the sportsman, for two weeks of camping, must have buffalo skins and blankets, kettle, tin plates, cups, and such things, together with bacon and bread to last a few days. After that he should trust to his skill in killing to supply the board. Also, he requires a moderate quantity of tea. I believe some carry with them a small keg of whiskey; in fact, it is considered by many a necessary article on these occasions, as it is impossible to drink the lake water on account of the profuse vegetable growth of rice, lilies, and other plants and flowers, which are almost invariably present in these small lakes, and certainly add to their picturesque beauty. Having towards evening collected our necessaries, we began to look for Mr. Thad., who had, unnoticed, strayed from our path.

We had in prospect that night a drive of seven miles in a wagon to Bridgenorth, a village consisting of one small tavern and a boat-building shop. We wished to set out as early as possible, so as to obtain a good night's rest and be prepared for a long paddle the next day. Thaddeus, however, was not to be found, and after a diligent search we went without him, taking with us his rifle and cartridge box, and leaving word to have him taken out early in the morning in a buggy. It turned out that the young man could not refrain from visiting an acquaintance of the fair persuasion, and once in the charmer's fascinating presence he found, no doubt, it was impossible to resist the spell of her enchantments, and midnight had stolen in upon the happy lovers ere Thad. awoke to the slightest degree of consciousness.

Determined to start that evening, we loaded our wagon with two canoes, ammunition, and other supplies, and ourselves, three in number, besides the driver. The wagon that held all this was very moderate in size, with easy springs, but the canoes are carried in a peculiar way. Two poles are placed across the wagon above the box and nearly over the axles. The poles extend about three feet on each side of the wagon box. Across the poles the canoes are tied, one on each side parallel with the conveyance. Thus, the seats are left free. Away we went, singing merry songs, and it would, I am sure, be hard to find "three blyther lads" than we.

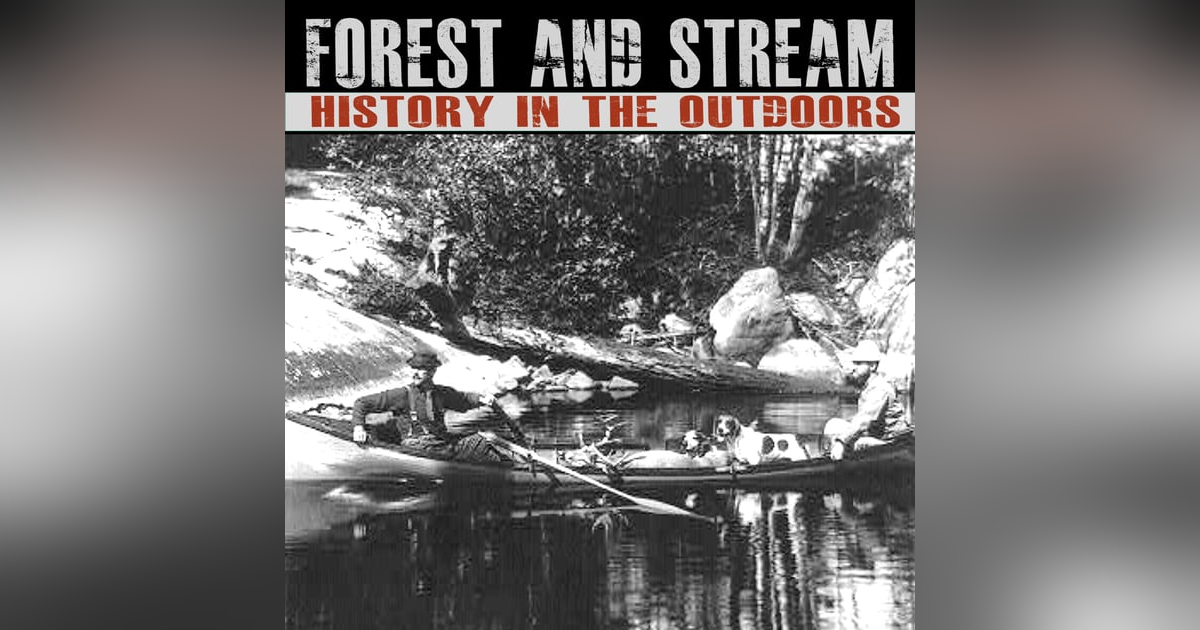

After breakfast the next morning at Bridgenorth, on Chemong Lake, having waited a short time for the delinquent Thad. , and upon the arrival of the repentant youth, about nine o'clock, we gaily proceeded to load and trim our canoes. Having arranged to follow this chain of lakes about forty or fifty miles before settling upon a permanent camping ground for our labors, we set out, Frank and I in a birch bark canoe well laden with our guns, ammunition, and camping utensils, besides the two hounds, Woodman and Harry, in the bow at my knees. The wind was pretty fresh, and blowing directly against us, making the paddling rather hard work, and also making the water so rough that a good deal of it was shipped over the bows. This disturbed the dogs considerably, and I was obliged when they would attempt to get up on the bow to keep them down by dint of a few sharp blows on the head with the paddle. The wise creatures, however, soon became accustomed to it, and, as if they knew for what purpose we had embarked, behaved like noble martyrs.

The roughness was so great that Frank and I, as well as Benton and Thad., in a broad canoe, were compelled to pull ahead as strongly as we could from island to island, and from time-to-time unload, empty out the water received over the sides of our light crafts, load up and off again. Thus, about nightfall, we got to the foot of the lake, where we pitched our tent and tarried for the night.

Chemong Lake is within the pale of civilization, the land on either side being cultivated, and some comfortable looking farm houses being within the view. The islands are numerous, and are covered with shrubs and small trees. Some of these islands are almost perfectly circular, and seem to rise out of the water like mounds, with the trees so thick and even that they often present the appearance of a beautiful green cone of foliage floating on the surface of the water.

We rose in the morning a little before dawn, and the industrious and enthusiastic sportsman, Ned Benton, sallied out in a canoe to make war upon grey-backs and mallards, while the rest of us remained to pack up and arrange for the morning meal, and as, occasionally, we heard the report of our companion’s gun, the light hearted Thad. would exclaim that should he get two or three brace of ducks he would give us a stew that would make us feel like princes. In a couple of hours Ned came in with five beauties. Thad. made good his boast, and as he danced around the fire preparing the savory meal he seemed to us (unaccomplished in the art — I was almost going to say the divine art — of cookery) clad in some mysterious power.

During the night the water had become quite smooth and we glide off. We send the canoes along with ease. Everything is calm and quiet. The sun bathes the woods that line the shore in the mellow light of morning. Fresh and soft and pure looks the foliage, as if it had sprung up like magic. Nothing is heard save our chatting voices and the musical ripple of the water, as the canoes shoot through it. Truly we feel like princes; if not as rich at least as independent.

Soon we arrived at a mill-dam, at the outlet from Chemong to Buckhorn Lake, owing to which we have to make a portage. Unloading, we carry our packs and canoes nearly half a mile, and then embark in another water. We did not go far before we came to the Buckhorn Rapids down which we ran in beautiful style, Thad. giving us a lead. Frank and I followed in the birch bark, and Benton brought up the rear. On the right is a large mass of rock which rises perpendicularly from the water about forty or fifty feet, and extends along the shore as many yards, sloping down like the roof of a house, and meeting smaller rocks and a rich growth of woods; on the left the water is full of boulders, and the shore thickly lined with young trees and shrubbery close to the water's edge, and even appearing to extend into it.

These rapids are comparatively swift and full, but with scarcely any turns. I laid my paddle across the bow and allowed my friend Frank to pilot us through; and it certainly required no small skill in steering and handling the paddle. The sensation was truly pleasurable, and is difficult of description. At first the canoe moves slowly and evenly along of its own accord, without any assistance from the occupants, increasing in speed through every foot of space; then entering the rough waters of the rapids it shoots off like the rush of some living creature let loose from its bonds; then, making a turn between two impending rocks, it darts past within a few inches of one of them, and then, in the deepest and strongest force of the current it bounds gracefully along on the waves, as if glad that it requires not the hand of man to give it motion; and, having acquired this magical independence, it seems to leap from wave to wave, dancing in rejoicing playfulness to the tune of the singing stream till it loses its joy and force and strength in the calm waters of the rapid's foot.

Once more we ply the paddles with some degree of force and gracefully glide through the waters of Buckhorn Lake. The advanced morning is splendid in the radiant beams of the warming sun. The small bays that indent the right shore, skirted sometimes on one side with large flat rocks and on the other with heavy forest trees, are entered by rivulets from the wilds and hills beyond, visited only by Indians and adventurous sportsmen. Here all traces of civilization are passed, and the whole prospect is one of primeval nature. Pulling the three canoes abreast we pursue our way in happy commune. "We leave Deer Bay on our left. It is the largest on the lake, thickly covered with rice, and its shores closely grown with trees of various types, looking in the calmness of noon time like a close wall of leaves defending the peaceful water from all intruders.

Now, for a mile or two in length, the right shore rises in a sloping hill, nearly two hundred feet in height, giving the effect of a vast, closely wooded slope from the beach up, appearing to extend grandly and proudly to the silver-bordered clouds that rest serenely upon its summit. Taking a turn to the left we hear the rumbling of another rapid, and after holding a consultation as to the proper channel to run, we go down singly, Thad. again proceeding in the van. We conclude to take the side channel, and gently floating through the softly moving sweep of water at the head we turn by the edge of the rocky side with the increasing movement of the current, apparently about to rush against the parapet of solid rock in front, when the stream, by a sudden swerve, as if in merry caprice, bears us around, and then, as if angry at having carried us in safety through twists and turns, sends us with the force of its full speed over the collected volume of its bounding waves, and we enter the strangely named Lovesick Lake.

Here we met another party of hunters, like ourselves. It seemed so strange— as if they had sprung up from the water by some magician's wand, after moving the whole day through scenes of enchanting wilderness and peaceful, quiet beauty, which had never in all the roll of ages been disturbed by the innovations of man. They were going, they said, to the rice beds on Deer Bay for the evening duck shooting. They told us where their tents were pitched, and advised us to establish ourselves on an island opposite theirs, which we agreed to do, having concluded previously to make this lake our permanent camping ground.

Frank Stalwart had known these gentlemen for years, and hence the greeting of him and his friends was cordial indeed, our canoe and theirs having been drawn up close together. Like us, they were four in number. They told us they had that morning (their first one out) killed a deer, and it was agreed that they should visit our camp in the evening to arrange for a deer hunt in one party the following morning. It was about four o'clock in the afternoon, and in a few minutes after, we reached the island of our destination, where we at once proceeded to unload our canoes and pitch our tent. This island was one well adapted for our purpose, being elevated and dry. From where we landed the approach to the level above was steep, but the ascent made without difficulty; On the other side the rocks were perfectly perpendicular, and rose directly out "of the water about thirty feet.

The tent having been tightly fixed, Frank and I selected a trolling hook and line and started off in search of fish, proposing to return in about half an hour, while our two companions prepared the evening repast, passing around the point of the island, we move under the high overhanging cliffs that skirt its side; then, as we near the border of a large rice bed, I let out the trolling line in hopes of securing the prey. In a few minutes, while Frank and I were cementing our friendship with mutual assurances of a constant attachment in the future, I felt a sudden jerk, then, as I took a firmer hold of the line, a stubborn pull. Knowing the cause was an active maskinonge, I began to haul in. Feeling the resistance, he darted forward, then to one side with a wonderfully strong plunge. As I brought him near, he bounded to the surface in frantic efforts to get free, and gave us a very liberal sprinkling. A couple of quick pulls, however, and a good steady haul, laid him captive in the canoe, when, with a last desperate whisk of his tail he snapped my briar wood pipe in two like a piece of thin glass and sent the pieces flying in the air.

Thus ended the history of my favorite pipe, which was carefully strengthened with a silver ferule, and thus a plump twelve pounder of the finny tribe was lost to his companions of the deep to satisfy the selfish sport of man. After catching one or two more I roll up the line, and we quietly take a sauntering sort of paddle about the edge of the lake to drink in all the native beauty of the view. I think neither poet's pen nor artist's pencil could fully and clearly describe the delight that fills the mind, or the peculiar thrill of serenity and pure sensation of awe that stirs the heart and moves the thought to involuntary devotion in such a scene.

The water is as calm and smooth as a sheet of glass, supporting on its even surface large patches of rich full blooming lilies of spotless whiteness surrounded with their broad, deep green leaves; and very carefully, without knowing it, do we dip our paddles so as not to mar their matchless purity nor disturb the sweet repose of floral beauty at rest upon the water's bosom. It seems a wanton sacrilege to displace the fair ornaments with which nature has adorned herself. The lake side is closely lined with rocks and ledges of uneven height, from out whose crevices grow tall pines and large firs without the slightest evidence of soil. The water is deep quite up to the rocky shore, and the intervening spaces between some of the moss-covered, sloping rocks are filled with a luxuriant growth of trees of numberless shapes and sizes.

The autumnal variegated tints of orange, yellow, scarlet, green, and red, intermingled with the unaccountable harmony' of Nature's marvelous work, contrast so pleasingly with the deep and constant color of the foliage of the heavy evergreens. These rocks and wooded growths are high and close, and nothing can be seen over or between them. There is almost an angular bend at this part of the irregular shore, forming, as it were, a temple for the appearance of the divinities of the place.

The evening is impressively still, the water is supremely calm, like the innocent sleep of a fair infant; the mild subdued light of the receding sun produces the shadows of the objects in view, inverted beneath the lake; our paddles are quietly, tenderly, with sacred care, placed across the canoe; our friendly talk is hushed; we are as motionless as the placid lilies that surround us ; we are lost in the sublimity, the grandeur of Nature, fast bound in the awe of the majesty of her magic spell.

At length the approach of falling night reminds us of our companions in the camp, and we return to our tent upon the island, exchanging, as we go, expressions of wonder and admiration. In the evening we gathered drift boards from the island and made seats around our camp fire, while arranging which the measured sound of paddles, and the steady hum of voices met the ear. We immediately proceeded to the shore, and there met our acquaintances of the afternoon.

Their canoes pulled up, we all formed a pleasant social crescent before the fire, the can having been previously hung above the blaze in readiness for a brew with which to welcome our sporting guests. The night was cool and frosty, not very bright, yet myriads of twinkling stars sparkled in the deep blue sky. No lights or signs of any kind gave token of civilized life. Our small party of eight, gathered from various quarters of the globe (some of whom had travelled in many climes), had met on this tiny islet in a small lake, surrounded by miles upon miles of the untouched wilds of Nature, and no sound was heard save the constant rushing noise of the swiftly flowing rapids. There was Major Howard, an Englishman, now living in the neighborhood of Peterborough, and Mr. Loring, a civil engineer of the same place, with others of lively and social predilections, who all told interesting and romantic incidents of foreign travel, as well as sporting and hunting experiences in the wilds of Canada.

In the clear bracing air of the autumn evening, as we smoked our pipes and sipped the warming beverage, our talk became readily savored with the hunter's phraseology. "How clearly," said the Major, "we can hear the tumbling of the rapids; the night is so calm. That point, you know, just at the head, used to be a favorite camping ground, but of late it has been rather abandoned. There have been several drowned in running through. Two poor fellows were lost the past summer: "And why didn't they learn to swim," put in our Irish friend, Carroll, "or not go poking themselves into traps they couldn't get quietly out of again." "But my dear fellow," replied the Major, "the eddies are so strong, you know, that even good swimmers have rather a frail chance; and as for guns, why bless your heart the foot of these rapids is fairly paved with them." "Are you an experienced canoe-man, Mr. Bertram," the Major continued,' addressing me. "You're not? well, you'll soon like it. It's a fascinating life, I assure you. Upon my life, Mr. Bertram, it's a very fascinating life; so free, and wanting care. Why, we come up here every few weeks and take down a deer or so, and a score or two of ducks. It is really very jolly, and no end of sport." "Do you remember, Frank," said Loring, "when you and I upset on Black Duck Lake?" "Indeed I do, old boy, and I feel chilly every time I think of it." And then was told, at some length, how they dived and recovered their guns and some of their other traps. "I suppose you were rather moist at the time," said Carroll, "but it makes a very dry story." Then the tin cups were soon replenished from the steaming can and passed around the circle. "There's one thing true," said the incorrigible Carroll, "it would never do to drink this lake water until it was boiled down." And so the talk went on — of yachting in the Mediterranean, racing in England, and social converse concerning mutual friends and acquaintances — till we separated, about eleven o'clock, having settled to meet at dawn ready to chase the deer. Then we spread our buffalo skins on the ground in the tent and retire for the night, well covered with blankets, beneath which we slumber soundly till the break of day.

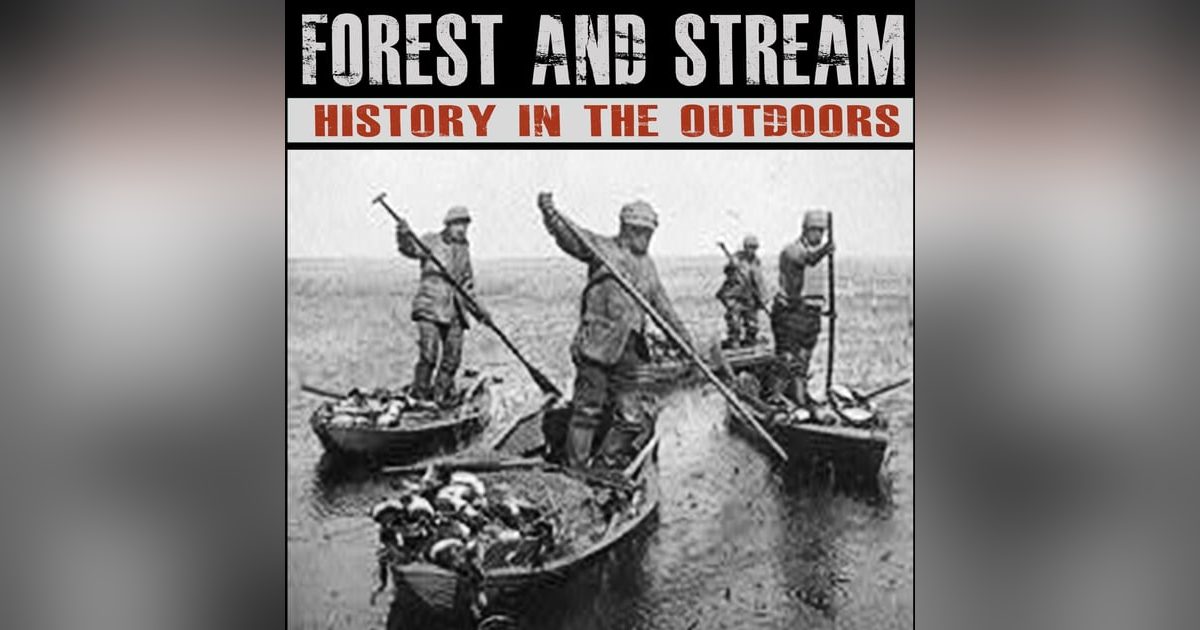

The mouth or door of the tent being open, we behold, on awaking, the waning stars, not yet entirely chased away by the fast-approaching sunlight. A hasty toilet made at the lake, a hasty breakfast, and we are ready for the start. Frank Stalwart and I were stationed with our canoe at one end of our own island to meet the deer, if one should cross from the main land, and as we sat quietly waiting beneath an overhanging growth of shrubbery, projecting from a ledge of rock, said he, "Rob, did you ever hunt the deer before?" "Not in this way, Frank; I have generally hunted in run-ways." "And," he replied, "a run-away business I expect it was, was it not?" 'Well, it was not so much their timidity as my ineffectual aim." "It is time, then, you had an aim in life. But you may be more successful in this method, as you get them at shorter range." "I understand," said I, "the general theory of this mode, but will you be kind enough to give me all the minutiae?" "With all the pleasure in life, old chap. It is in this way: — Well, there should be about five or six canoes and four or five hounds, and it is very fortunate for us we met these other fellows, as they make the party about the right strength, and afford us, with our own, the proper number of dogs. There is always an injunction understood that no firing is to take place on the morning of a hunt, as these denizens of the forest are very timid creatures, and avoid the direction whence any noise is heard. So, remember if a half score of ducks fly under your nose you must let them pass. The guns should be loaded with buckshot, although experienced men kill sometimes with small duck shot. The canoes are stationed at different points, where the deer are likely to cross. This morning one is placed at Scow Island, half a mile or more to the right, one down in the bay, about half a mile to the left, one out at Black Duck Lake, nearly two miles away, and others I know not where. Two or three of the party go on the main land to put out the dogs. Thad. , Loring, and Riggits are doing that arduous duty at the present time.

When the dogs strike upon the scent of deer they are let loose. When they get within hearing distance the deer break from cover and almost invariably make for the water as a harbor of safety from their canine pursuers. As soon as the does give tongue the men at the different stations are to be on the alert, and when a deer enters the water at any particular, point the man who discovers him must keep perfectly still until the animal is well out in the lake, as the deer's senses of smell and hearing are extremely acute. Then the canoe, quietly and with as little noise of the paddle as possible, meets the intended game, until observed by the unsuspecting creature. Then the pursuer flies after him with all the skill he has in his power till he gains within a short distance of his prey. Then an unmistaken aim and the discharge of the fowling piece lays the forest monarch low."

After faithfully remaining at our post about two hours or more, we heard the yelping of the hounds, which made us more sharply attentive. It was soon evident, however we were not to have the good fortune of a chase at our station that morning, for ere long there came from a distance the report of guns. Then we knew the hunt was over, and we repaired to the tent. In about three quarters of an hour the rest of the party came in, and one canoe was the honored bearer of a plump young doe. After a time, the dogs made themselves heard on the main shore opposite, and the active Thad. quickly proceeded to bring them over.

So ended the morning's work. After the midday meal we sat and smoked, or lay on the blankets basking in the sun till four or five o'clock, when we set out for the evening's duck shooting, some of the party remaining near the camp and others going up to the large rice bed near Deer Bay. And the party reassembled in the evening well rewarded with game.

Thus, we spent the time; and richly did we enjoy the days as they passed. Indescribable was the pleasure of hours upon hours every day in the clear open air and sunlight, with the exhilarating exercise of paddling, the inspiration of the scenery, and the excitement of the sport all commingling their various charms. We were well able before we left to verify the words of the Major, for truly did we find it a fascinating life. Our freedom was perfectly unalloyed. We had no cares of business nor the exactions of the conventional pleasures of society. Liberty was there unbounded. But now I will not make any further narration of our camping expedition, but in another paper may say something of the conclusion of our journey and the romantic interests of these spots of nature so beautifully wild.

Rob Bertram